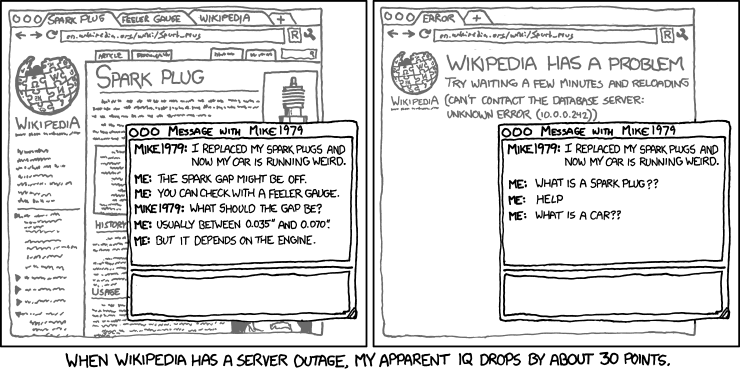

On August 3, I was flipping through kxcd’s nerdiddlyumtious comic archive, and decided to share this one on my facebook wall. By the time I checked my account the next day, my wonderful CogSci friend from university and bona fide IT maven, Vladislav Sekulic, had responded with these praiseworthy posts:

Vladislav Sekulic So true! Brings up interesting issues. Compare Mike1979 chatting with his Wikipedia/Google-savvy friend to an actual car mechanic/expert. Suppose he gets the same advice and answers. Does his internet savvy friend know as much as the mechanic about car repair?To narrow down the situation here a bit. Let's say his friend could always have the internet handy and could find any declarative piece of information that is relevant regarding car repairs. Or if we're talking about the medical domain, suppose additionally that the person one way or another has free online access to any scientific journal they could care to search, and can obtain/borrow any textbook that is typically assigned to novices in the domain of interest. Assume the person has a modicum of scientific ability and critical thinking, can write well, etc.Would this person be able to answer any question or present a good argument for a given position regarding these domains? I.e., aside from declarative knowledge, is there a component to expertise in a domain that is a superset and cannot be acquired except through actual practice of the domain?For control, let's further assume that procedural knowledge is not relevant, i.e., the person does not actually have to be able to repair an engine or perform a heart transplant, they just need to be able to give step-by-step instructions on how to do the same, or give advice about it, or argue why a certain procedure is not optimal in some way, etc.One reason I've wondered about these issues relates to self-proclaimed "experts" who blog or otherwise put information online about an opinion they have on a subject, whether politics, climate change, health, or otherwise. They may present a cogent argument, and give good evidence, even going so far as to quote papers from reputable scientific journals. Nevertheless, they do not have formal training in that field.Some people who would read their opinion would not care about that, and only be impressed with the actual arguments -- though, to be fair, in many of these cases I'm sure there is some implicit confirmation bias that the person held before even reading the piece. But others would disregard the argument out of hand simply because they do not have the relevant credentials, regardless of the substance of their reasoning. Who would be right?Sometimes such a self-proclaimed expert will be able to (seemingly) successfully spar with an actual expert in the field. This is perhaps most readily apparent on climate change denier blogs. To a lay person or amateur, it may seem that the blogger and the scientist are on equal footing. But perhaps this would not be the case with a third-party observer that is also an expert, say an actual climate scientist (I can't think of a real example, this is just hypothetical and may not actually happen, which is telling in itself). They may find it "obvious" that the blogger is way out of league. For example, they would never actually endorse their post to be published in an actual scientific journal -- *aside* from any considerations regarding the person's credentials, i.e., rejection on the basis of the writing alone.Again, our climate change denier blogger has all of the abilities I've attributed to them above (full online/journal/textbook access). And I know, I've switched from car repair to climate change, but they both relate to expertise and I hope can be addressed in the same way (or not?).So, what is the difference between the lay person who sees the online climate change dispute as legitimate, and the expert who sees the climate change denier blogger as being "obviously wrong"?Is there something really silly about the situation as I've presented it?Am I totally procrastinating right now??August 4 at 8:34pmVladislav Sekulic I see it as a bit of an "information age" version of a Chinese Room, but am ultimately most interested in the nature of expertise and, importantly, credibility, which has obvious social implications.August 4 at 8:37pmVladislav Sekulic To be fair, I should give a stab at this first. Prima facie, I would say that one difference is that although the super-blogger and expert can have access to the same factual information, the latter has had time to integrate this information in such a way that they can find connections that are not readily apparent, and can see the "big picture" that lets them reason in a way that is more veridical. Although, to be sure, even (and especially) amongst experts, there can be deep disagreements about the "big picture", so perhaps this consideration is not a good one.August 4 at 8:46pm

Given the time and thought that Vlad had

already invested in this conversation, I decided against standard facebook

protocol (which typically involves a crass one-liner by way of reply) and bagan

typing out a more suitable response. Before I knew it, my reply had swelled far

beyond sensible facebook post length, even by our own outrageously verbose

standards. With my own post nowhere near complete, Vlad and I were joined by

the brilliant Tristan Nixon:

Tristan Nixon I think your last comment is the most telling. A person who searches online for a practical piece of advice, and then parrots the answer to a friend does not really "know" the answer to the query - they are simply acting as a proxy for the internet's "knowledge". A mechanic (one hopes), not only knows a lot of practical advice about cars, but also has a sophisticated and detailed mental model which unites and organizes that knowledge. They aren't just parroting facts from a big database in their heads, they can use the model to generate an indefinitely large set of different suggestions, advice, predictions, diagnoses, etc. about cars. Its a competence vs. performance distinction. A lay person may have a sufficient model of a car to be able to digest and understand a certain piece of information about spark plugs, but their ability use their limited model to adapt to novel and unforeseen issues is going to be much less.August 5 at 6:51pmTristan Nixon As for climate change denier bloggers, I think there's a small handful of amateurs who actually have a fairly decent understanding of the science, and make a few good critical arguments. There's also a whole lot who know very little and who make overly simplified arguments that appeal to a lay audience precisely because they give the illusion that these issues are simpler and more straight forward than they really are.August 5 at 7:12pm

After nearly a fortnight’s worth of

typing, procrastination, thought, and delays, I finally posted my response

as a facebook note.

Needless to say, I have yet to receive a

response. :-)

Instead of having you click through to

the old note, I’m copying the whole thing below. While facebook’s intellectual

property issues provide enough justification for this redundancy, the main

reason that I’m putting this up here is that I had accidentally switched “Mike1979”

and “Me” in my note. This glaring error is corrected in the version below.

Hey, Vlad! Howdy, Tristan!

Awesome of both of you to incite

intelligent discussion on my wall; a sorrowfully rare commodity on facebook. I

decided to take my time replying. Work has been kind of hectic, and given the

discussion, I didn’t want to provide an ironically simplified response. :-)

I think there’s more than a couple of

things going on here. We’re comparing two types of question-answerers. There’s

the expert, who has had (over 10,000) hours of engagement with the subject

matter; quite likely a mix of hands-on, real-world interaction, application,

and formal or otherwise declarative instruction, self-instruction, research,

and the like. Then there’s the “internexpert”: a veritable search guru that’s

never left his/her apartment, and whose mother takes care of all the chores.

As Vlad pointed out, it feels a bit like

the Chinese Room, and I’d like to add that it also overlaps with Frank

Jackson’s “Mary’s Room” scenario. Does the tablet-transferring resident of the

Chinese Room “know” Chinese? Does Mary the Chromatologist-Neuroscientist “know”

what red is? Does Mike1979’s friend “know” what a sparkplug is?

I’d guess that most people would answer

in the negative. It seems unlikely that there exists any kind of expertise

that’s wholly declarative. Even expertise in activities like reading or writing

(and, yes, ‘rithmetic, too) involve a mandatory procedural component.

Also note that it would be a mistake to

equate “knows” and “is an expert in”. I’m not saying that either of you have

claimed this, and just want to clarify how many questions might have been

raised here.

Back to Mike1979’s friend (for

convenience, let’s call him Ike1984). If he can respond to routine declarative

inquiries in more or less the same amount of time that one would expect of an

“automobile expert” (a general term that could mean auto mechanic, car

aficionado, etc. depending on the question posed), or even as quickly as

someone with a middling level of relevant internalized information, then at

least from the black-box perspective of his curious comrade, Ike1984 “knew” the

answer to the question.

Making another calculated guess, I expect

that most people wouldn’t be comfortable with this inference, and would say

something like, “No he didn’t! He doesn’t know anything about cars! He looked

it up!” To this, proponents of extended-mind-type theories would retort by

pointing out that the required information’s storage medium matters little, if

at all. The disgruntled deniers might even back their claim by reminding us

that a mere internexpert probably won’t remember the retrieved information

after ten minutes, let alone ten days. However, once we’ve reached this point,

the argument is no longer fair. One of our premises was that the external

information source is available readily and perpetually. If this is truly the

case, then the claim that internexperts are forgetful falls flat. Incidence of

Internexperts’ Amnesia is a function of server downtime.

At one point in your comment, Vlad, you

ask whether an internexpert would be able to “answer any question” or “present

a good argument”. I assume there’s a silent “...that an expert could?” and

“...comparable to that of an expert?” at the end of these questions. Keeping in

mind the time constraint mentioned above I’d answer “No” for the first

question. Unless the external resource already has the information elaborately

encoded so that not only are the subject matter’s “axioms” stated, but also

every one of its “theorems” that the internexpert might conceivably be asked to

provide. Even then, an internexpert would not be able to apply such general

knowledge to a specific case, and would instead be limited to, at best, reading

off a list of examples that can be found on some server somewhere. This is

because unlike the genuine article, an internexpert cannot be expected to

possess the ability to “derive” the theorems from their constituent axioms, or

to “sub in” values for the theorem’s variables. Unless the requested theorem or

formula is listed in the external information resource, the internexpert cannot

provided it as a response.

I find the second question the more

interesting of the two. Could a human lookup-machine present a good argument,

give advice, or determine whether a particular course of action is optimal (or

perhaps even just “satisfice-tory”)? The reason why this question interests me

is the observed individual differences among novices, when given such a task.

Surely, some people are bound to be more successful than others at solving

problems in a particular domain in which they lack expertise. Furthermore, I

believe that if these people are “better novices” in general, then such

general-purpose facility is an important component in the complex of cognitive

function that we label wisdom Reaching back to my PSY371 essay, my

executive-summary definition of wisdom was approximately “the ability to solve

problems in the absence of expertise.”

More specifically as a response to the

original question, I’d say that an expert would certainly have a much higher

success rate when asked for advice, sound arguments, and other activities that

are founded on providing an informed appraisal in a specific context. However,

this does not at all preclude a sagacious internexpert from reasoning his/her

way through to potential answers, extrapolating from the retrieved declarative

data. Deriving from first principles, if you will.

I think there might be an added layer of

complexity to this story, though. It is important to note that while the

domain-specific knowledge accessible to the internexpert is exclusively

declarative (as our thought experiment assumes), a successful advice-giving

internexpert must also rely on domain-general, procedural abilities. While this

generality would technically make it incorrect to claim that such a person is

an “expert in tyrocity”, I’d wager that these people have developed these

general skills through experience, in a manner similar to acquiring

domain-specific procedural knowledge (expertise). These people probably

acquired expertyro status after 10,000 hours of problem solving practice, just

like experts.

One thing that seems unusual so far is

that any expert that has put in 10,000 hours of domain-specific practice has

undoubtedly gone through the same amount of time solving problems, albeit of a

specific kind. Why do such narrow-focus experts ostensibly fail to achieve

similar expertise in tryocity? The reasonable answer seems to rest on these

experts’ dearth of variety of solved problems. Simply citing overspecialization

feels only marginally satisfying as an explanation. Here’s a more interesting

way of stating something similar. While it might be true that these experts

have overspecialized, it is interesting to note that they spent their time and

effort attending to their domain-specific subject matter. Instead, I have a

hunch that a true expertyro emerges after 10,000 hours spent attending to the

manner in which problems are solved (whether by themselves, by others, by

machines, or in the abstract), as opposed to (or more correctly, in addition

to) attending to the problem’s subject matter. It might even be not that much

of a stretch to claim that this kind of developed competence is an example of

meta-expertise.

Now, on to the issue of self-proclaimed

“experts” (for the sake of convenience, let’s just call them “pundits”).

The defining difference between pundits and those whom we are comfortable

calling experts is that the pundits lack certain credentials that the experts

possess. Individuals in both groups vary in competence, prolificacy in

publication, academic responsibility, etc. I can’t think of a simple criterion

for separability here.

Another important distinction to be made

is that of pundits vs. internexperts. These categories are not mutually

exclusive, yet they are distinct. Since I’ve mentioned above that the epithet

“pundit” is used here in a manner that does not judge competence, it translates

to something like “enthusiast author in discipline x”. Such a person may or may

not be an internexpert, depending on how much they rely on external sources,

versus recalling from (wetware) memory, to provide appropriate arguments or

responses. While some pundits are indeed internexperts, others are not.

Among these are self-taught neo-luddites, who retain large corpora of

information internally out of simple necessity (i.e. because of their aversion

to modern forms of information retrieval, coupled with the prohibitive weight

and volume of paper). However, there are also those pundits that remember a

large portion of their subject of interest, despite frequently accessing

digital resources, and yet do not rely on these resources as an alternative for

brain-memory. This is where the line between the pundit and the expert begins

to blur. On the one hand, a self-taught, online-only amateur could consistently

produce sound arguments and advice while AFK, and on the other hand, a computer

illiterate ink-and-pulp librarian could be branded an inernexpert. It isn’t

obvious whether these people are pundits or experts.

The question posed is whether one ought

to heed the pundits (as much as one heeds the experts). While it’s true that

readers’ confirmation bias often comes into play while deciding who to listen

to, trust, or believe, this doesn’t help our investigation, since readers of

both pundits and experts are susceptible to confirmation bias.

When it comes to rejecting all pundits

outright on principle, this sounds like a low-effort heuristic used to minimize

false positives. While level of acumen does vary on both sides of a doctorate

(or any other degree), it seems reasonable to assume that incompetent authors

without credentials smartly outnumber their credential-holding peers.

However, this still doesn’t answer the

question of whether it’s right to exclude all pundits from a debate. Although

I’ll qualify my answer in a bit, I’d say that it’s not sensible to bar

competent amateurs from a discussion. Such a policy makes less sense with every

passing month. Sure, even as recently as thirty years ago, an amateur couldn’t

be expected to compete with a certified expert, things have changed

tremendously. Access to information has considerably levelled the playing field.

While disparity in information access still exists between countries, cities,

and neighbourhoods, knowledge is no longer hoarded by academics, or at least

not as successfully or tight-fistedly as it once was.

And now for my qualification. As with any

other, the appropriateness of employing the no-pundits heuristic hinges on its

utility. Is it worth the time and effort to check each claim made by every

participant? If the decision to be made is mission-critical and the debate is

high-stakes, then I’d strongly advise against a no-pundit policy. Relying on

arguments from authority isn’t sensible when faced with potentially

catastrophic consequences. On the other hand, if the “magnitude” of the

negative effects of accepting bad advice is below one’s tolerance threshold, if

time is short, and if the expected effects are reversible, the no-pundits

heuristic might be considerably more efficient. Another factor that would

probably influence the inclusion or exclusion of pundits is consensus. Are all

or most of the experts in agreement? Are some or all of the pundits opposed?

Does consensus not exist? Are there too few experts?

And then there are some other concerns.

Are the experts falling prey to the eponymous Expert’s Fallacy, failing to

consider something out of sheer tunnel vision? If so, it would be insightful to

at least hear the pundits out. Do the experts also represent a group of

stake-holders in the issue to which the pundits do not belong? Think back on

UofT’s debate over tuition fees, for example.

Vlad, at one point you mention possible

differences between the way a lay-person and an expert assess the quality of a

pundit’s article. Let’s consider two cases. In the first case, the

(blogger-)pundit possesses expert-level competence, and in the second, s/he doesn’t,

but has some other means of impressing readers (e.g. skill in rhetoric). To the

lay-person, the pundit’s blog seems legit in both cases. As legit, in fact, as

the pundit’s arch-nemesis, Dr. Expert Ph.D.’s blog, which by sheer coincidence

happens to be hosted on the same blogging service, using the same CMS. To the

lay-person, the authors are evenly-matched adversaries, locked in literary

battle, and even fighting on (or for) the same turf. There is no outward

indication that one might be witnessing a scuffle between a prize fighter and a

back-street brawler, whether or not that’s actually what’s going on.

Now along surfs Dr. Alsosmart Ph.D.,

paying a visit to both blogs, just like the lay-person. Whether the pundit is

competent or not, Dr. A. will know. If s/he’s not, the response is simple; stay

away from this quack, prescribes Dr. A. However, if the pundit is providing a

well-reasoned, cogent argument, providing thorough, appropriate citations, and

is upholding a reasonable standard of intellectual responsibility, then a few

things could happen. Dr. A. might show approval, claim that the pundit’s

arguments are sound, and attribute the ideas therein to the rightful author,

which would be downright decent. On the other hand, Dr. A. might react in a fit

of denial, claiming that there’s no way an untaught ruffian could know what’s

what, and so the argument is bunkus, QED, which would be downright dastardly.

Another possibility is that Dr. A. decides that the pundit’s post isn’t worth

the time it would take to read it, and instead moves on to peruse several

peer-reviewed articles in prestigious journals. So long as Dr. A. does not

claim that the pundit is wrong or oughtn’t be listened to, this move is

pragmatic and fair, especially when time is short and there is more reading

material out there than one could be expected to read in a lifetime. If you’re

interested in reading more about ways that academics decide what to read, check

out stuff by Warren Thorngate, who’s at Carleton U.

It is also possible that an academic

might read a pundit’s article, and not endorse it for publication, even when

it’s well-argued and thoroughly researched. Sometimes the style is

inappropriate, or the tone fails to display neutrality, or something else of

the sort. In short, a blog post is a far cry from an academic paper. This

should come as no surprise to anyone, and is an important reason for blogs to

exist, even if academic journals accepted, reviewed, and published any

acceptable article from any person. Blogs are often intentionally informal and

easy-to-read at the expense of some measures of technical correctness. While

this is a legitimate reason for an expert to deem an article unfit for academic

publication, it does not discount the quality of the arguments its author presents.

So, Vlad, if the scenario you’re assuming

involves an amateur and an expert both assessing the quality of a pundit’s blog

post, it’s important to know whether the author is also an internexpert. If so,

that means s/he is simply looking information up online, and flinging a barrage

of facts at others that hold contrary points-of-view. If, on the other hand,

the responses provided are not just parroted statements, but are instead

robust, thought-through inferences, then credentials or not, the blogger’s

claims ought to carry some weight.

There might be some important differences

between expertise in climate change and car repair. When a car malfunctions, we

can take Dennett’s “design stance” and investigate, since we have sufficiently

complete knowledge of its design. This is something that we can’t accomplish

with climate anomalies at present, despite some recent and significant strides

forward in climate modelling hardware and software. Another difference that

comes to mind is the car expert’s ability to point out context-sensitive

exceptions. An internexpert would almost certainly be horrible at this. Imagine

an internexpert instructing a wealthy simpleton on changing the sparkplug in

his rear-engine sports car. What’s under the hood? Nothing! I’d guess that most

internexperts would recover quickly from mistakes like this (especially given

enough practice and encountering enough exceptions in a particular domain),

often by asking for more context-specific information from the other person. On

the other hand, most bona fide experts wouldn’t make such a mistake to begin

with.

I just remembered an example of something

like this happening to me. A few years back, I bought Myst IV - Revelation, the

PC game. It was a 2-DVD install, and it kept crashing on me; something that I’m

usually pretty good at fixing, or if all else fails, Googling away. This time,

though, I was stumped, so I relented and gave a call to Ubisoft Montreal. They

gave me a few tips to try, which didn’t work. After sending them some system information,

though, they figured out what the exceptional situation was that kept killing

the install: on my computer, I had My Documents mapped to D:\, a separate

partition, which has always seemed to me a sensible thing to do, in case...

wait, who am I kidding?... when Windows needed to be reinstalled. The game’s

save-file directory was hard-coded to C:\Documents and Settings\[user]\My

Documents (for shame, Ubisoft!), and so I had to switch my system back to this

default just play the game. There probably isn’t a resource that an

internexpert could use that covers an exception like this.

Now for an aside: while probably

rhetorical, I thought it was cool how the answer to Vlad’s final question is

continuous, not discrete: whether you’re procrastinating is relative to what

you’re supposed to be doing. :-)

I do like your closing comment, Vlad. I

agree that knowledge integration and “zooming out” to get a bird’s-eye-view are

marks of an expert. Even when there isn’t much inter-expert consensus on the

terrain, each expert can still pull back and find paths through their own

mental map of the domain. The internexpert’s external memory source, even if

well-written (and/or drawn), fails to provide such a well-integrated,

association-rich representation of the domain.

Perhaps the expert’s edge can be weakened

if the internexpert swapped out the web-based, thoroughly hyper-linked

super-wiki that I’d imagine Super Ike1984 would use, and replaced it with with

a relational database of everything on the Net; some kind of SuperOracle. Not

only would “atomic” information retrieval (like the wiki-search scenario above)

be possible, but complex, multi-variable “molecular” queries could be performed

as well. It would be like a wiki page that restructures itself to maximally

conform to the search parameters. The problem here is that in order to track

down the requested information, the internexpert would need to be, at the very

least, an expert in SQL or something similar. While this expertise isn’t in the

domain of the requested information, it still places more expectation of

competence on the person than in the case of the wiki-searcher.

What if we slapped a natural language

query parser onto SuperOracle, and gave it a wiki front-end? For one, becoming

and internexpert would be so easy that anyone with Internet access would be one

whenever they were online. I guess that means that the only human consultations

would be internexperts (i.e. everybody) asking experts questions that

SuperOracle still can’t track down or synthesize.

Tristan, it looks like I’ve already

touched upon some of the ideas you mention in this unreasonably long note,

largely in agreement. Coping with novelty and the unexpected is certainly an

advantage that the expert has over the internexpert. Sometimes I try to explain

to others how much of a role the current contents of our mind play in

interpreting incoming sensory information, and that each of us truly sees and

otherwise senses the world around them rather differently than others do. In

one tack I use with people I know, I draw their attention to how much their own

perception, language, and communication turns on and is filtered through their

strongest areas of expertise. One person might describe the unfamiliar as a

“whole ‘nother ballgame,” while someone else might find it “worlds apart” from

their usual surroundings and behaviour. Depending on who you ask, neurons are

like trees, trees are like neurons, or both are like Fibbonacci numbers. Oh,

and who could forget: “The Internet not something that you just dump something

on. It’s not a big truck. It’s a series tubes.” I really wonder what Senator

Stevens did for a living before taking office. Heh, not to worry; I’ll “know”

once I Google it. ;-)

One thing, though: what do you mean by

“competence vs. performance distinction“ here? I’m familiar with the

distinction in other contexts; I’m just having trouble mapping it onto the

current discussion. Usually C vs. P comes up during discussions about variation

in the task performance of a single individual across a number of trials. It

seems like you’re using it in an individual-differences comparison. I’m

probably just not following you here.

I think your comment on the

attractiveness of oversimplified arguments is cool, Tristan. It seems like a

sibling of confirmation bias. Maybe it should be called “comprehension bias”:

one is more willing to accept something they can easily understand than

something that requires greater effort to comprehend. Hey, there might be a

psych experiment in there, eh?

Lastly, just a few hours before I shared

that xkcd comic, I read an interesting article on Wired about the Flynn Effect

(http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2011/08/are-smart-people-getting-smarter/).

It suggests that unlike previous theories had suggested, it isn’t just the left

tail of the distribution that’s improving on IQ scores; even smart people have

been getting smarter. On tidbit that got me thinking, and that is rather

fortuitously relevant to the current discussion, stated that “[IQ scores have]

actually increased on measures of fluid intelligence”, as opposed to

crystallized intelligence. This made me wonder whether the Flynn Effect could

be the doing of a world abundant in external information sources as well as

information encoding facilities. I’d imagine that such ubiquity would ease off

the evolutionary pressure that has undoubtedly applied to humankind for a few

millennia: the need to memorize. The freshly-fallowed cortical fields resulting

from this ebb in demand for crystallized intelligence might have allowed these

resources to be taken up by a competing cognitive-evolutionary pressure: the

need to process novelty. This seems to explain these reported increases in

fluid intelligence. If so, it might be time to shift our collective

intellectual activities slightly further away from spelling bees and irrational

number memorization. While some might deplore how “kids these days” can’t

recite their multiplication tables, and though journalists have begun posing

questions like, “Is Google making you stupid?”, my opinion is that if our

unwitting policy of offloading memories onto external media is driving

humanity’s apparent neocortical resource reallocation in directions that favour

cognitive flexibility and coping with novelty, then these trends should be

celebrated. While there are certainly pitfalls to “information outsourcing”

(privacy, longeivity of medium, potential periods of inaccessibility, etc.),

such a move, on the whole, would probably be a positive one.

Okay, I’ll stop typing now. Your turn!

:-)

No comments:

Post a Comment